How did you get into this business?

How did you get into this business? It’s a question that has been asked of most, if not all comedians at some point in their careers. I’ve related my own story, off the cuff mostly, over dinner, with friends, but occasionally in a radio or TV interview. I’d never written it down, nor saw the need to? Recently two photos emerged of myself and my brother busking the very first show I’d ever written. It was called ‘The Human Anvil’ and was to give me a nickname that was to stick with me for the next thirty years. Today a British comedian who is completing a Doctorate on The Cultural History of Alternative Cabaret asked me – and many others I’m sure – to complete a questionnaire. The first question was basically ‘How did you get into this business?’

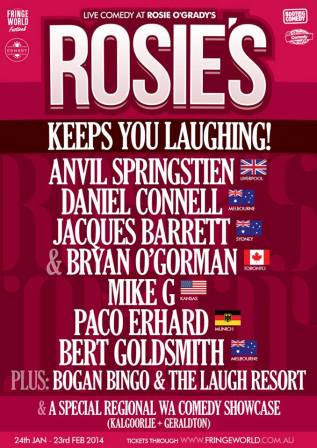

I reproduce both photos, and the questionnaire, in full below.

- When I first met you (at the Fish Quay Festival in North Shields, I think) you were performing The Human Anvil with Graeme Kennedy. How did that come about?

I’d been working as a driver/odd job man/stage hand for a community theatre company in Newcastle called ‘Skin & Bones’ over the summer play-schemes – remember them? It was now a few days before Xmas and I was broke and on the dole. Maisie Sharpe, an actor/administrator at ‘Skin & Bones’, rang to say that Pilgrim Street Fire Station were looking for a children’s entertainer for their kids party on Xmas Eve, “None of us can do it and I thought of you? Just borrow our stilts, face-paints, and the big parachute from The Children’s Warehouse next door. You’ve seen it done a thousand times over the summer, and it’s fifty quid, cash…”. Fifty quid? Cash? Xmas Eve? I just couldn’t say no, could I?

With two days to go, and a boot-full of stuff, I panicked and rang a guy called Nick Mumby. Nick had worked with Skin & Bones as a writer and performer but was now at a loose end. He was – and is – an immensely confident and competent character who was to become a life-long friend. I offered him twenty five quid.

Driving to the ‘gig’ – him increasingly excited, me increasingly fearful – Nick told me he knew of a great trick with a concrete slab, a child, a cream cake, and a mallet. We didn’t have a cream cake or a mallet, but I did have – for reasons best not discussed here – a rather large sledge-hammer in the back of the car. We stopped off under Byker Bridge – now a place of beauty and part of the ‘Ouseburn Valley’ development, then a repository for burnt out cars and fly-tipping. It took ten seconds to find the first pile of builders rubble and throw a concrete slab into the boot.

It was two and a half feet square by three inches thick and weighed seven and a half stone.

Two hours later I was standing under a huge green parachute, arms above my head – a human centre pole surrounded by a circus tent of twenty or so smiling, and quite badly painted, creatures of the jungle. I was an hour and a half into my first ever performance. The kids were loving it. The parents were loving it. I was loving it, too. Everything had gone perfectly. My fears had evaporated almost instantly. What could possibly go wrong? Nick bounced up from amongst the circle of creatures to replace my tiring arms with his own, “Go and get that slab out of the boot of the car” he whispered.

We quickly learned that seven and a half stone of concrete cannot be supported by the ribcage of a five year old. Still, Nick’s experience shone through, “Ha Ha! Only Joking! Tell you what kids… let’s get one of the Grown-Ups under the slab!”

We quickly learned that seven and a half stone of concrete cannot be supported by the ribcage of a seventy five year old retired Fireman with emphysema. Nick’s experience waned. “Nick? Nick?” I hissed. Nick’s eyes looked slightly glazed. So did the eyes of the retired Fireman with emphysema.

I’d never seen Nick stumped before? I took charge for the first time that afternoon, “Ha Ha! Only Joking! Tell you what kids… let’s get Nick under the slab!” The crowd went wild. Looking back, they really did think this was a seamless and seasoned performance – all the while building to Nick lying under the concrete slab, a housebrick standing upright in the centre of it in lieu of a cream cake, me towering over him, sledge-hammer in hand, both kids and parents chanting and clapping a count-down from ten.

I bottled out from hitting him at ‘two’.

“Hold on, kids, it wouldn’t be fun if I hit him, would it?” “No!” screamed the kids, “So… let’s get one of your Dads to hit him!”. To this day I’ve no idea what made me say that?

My jaw dropped as Thor went into action. The sledgehammer a blur as it moved through a perfect arc on its way to make contact with the exact centre of the end of the brick. He’d asked, as a casual aside as the chant reached ‘five’, how hard he could hit Nick. I’d said he could hit him as hard as he liked as long as he hit the exact centre of the housebrick standing upended on the slab. I honestly thought ‘give the punter a precision instruction, he won’t be able to get a good swing at it’. More fool me – I’d forgotten he was a Fireman.

Bang. The housebrick transformed itself into a cloud of red dust as the slab, initially moving downwards, exploded into the air in a myriad of pieces only to fall back to earth – back to Nick.

Nick lay motionless amid the rubble. From this cacophony of noise – silence. Deafening endless silence. A woman holding a baby to her breast whispered almost to herself, but was heard as a booming, pointing finger of accusation, “My God… in front of children.” I pictured the headline in the following days papers, ‘Children’s Entertainer Dies as Horrific Stunt Goes Horribly Wrong’. My career in the performing arts ended almost before it had begun. A noise? Was that a noise? The rubble moved… Nick moved. Nick moved again, then spat out a large piece of concrete from his mouth. I looked to the shocked silent audience, smiled, and screamed “Tadaah!”

All the way home I kept asking if he would do it again. His ribcage was badly bruised and scratched. He was bleeding from both hip bones and had burst a blood vessel in his left eye. Yes, but would he do it again if I was under the slab and he was swinging the sledgehammer? He said he might. I stayed awake all night and wrote a forty minute show where the hammer represents the cultural and industrial might of the masses which, when given the correct leadership and momentum, would smash through the stranglehold of international finance capital, as represented by the brick… Eight hours later I shuffled the handwritten A4 pages together and, after putting a staple in the top left hand corner, penned the title ‘The Human Anvil’.

Twelve months later I was performing it under the Eiffel Tower – with Graeme Kennedy as Hammer Man – for British television.

Funny how things turn out?

- Did you have any performance experience prior to The Human Anvil?

No.

- What was your first impression of Cabaret A Go Go* (be honest)? [*’Cabaret a Go Go’ – an eclectic group of people who first brought ‘alternative’ comedy to the North East of England. A.S.]

In all honesty I was in awe of anybody that was doing anything like this. I hope it didn’t show? I hope I looked cool – I was certainly trying to look cool?

- Were you at all influenced by punk or new wave/post-punk?

Yes. I thought that this, us, we, I, were part of that. We were the ‘new wave’ – that was us, ‘post punk’, exciting, dangerous, revolutionary, cool…

- How would you describe the counterculture?

Those last four words of the sentence above.

- Did the counterculture have any effect on you?

You have to understand that I’d come off a very large post industrial estate dominated both by unemployment and catholicism in equal measure. This was my Renaissance, my Enlightenment, my world turned upside down. There were battles to be fought – Thatcher was in power. Did I look cool? I’m sure I looked cool?

- What was your first gig like?

Awful. Died on my arse in front of four hundred drunken men. Got paid five pounds – two pounds fifty each. It cost fifteen quid in petrol to get to the gig which was in a dance hall on Tynemouth Beach. It burnt down shortly afterwards.

- What are your thoughts on the terms “alternative cabaret” and “alternative comedy”? Are they useful?

Maybe not now, but they were then. They provided us with a tag, a label that positioned us away from ‘them’ – the boring racist, misogynist shite that had gone before us.

- What kind of things inspired you?

At the time I just thought it was a mixture of anger and Marxism? I think, initially at least, we each inspired one another? After confidence overtook the anger I started to appreciate and be affected/inspired by individuals who had succeeded despite swimming in a sea of the mundane, Dave Allen, Les Dawson, Billy Connolly and all the other folk circuit comics/story tellers who laid the groundwork for our comedy to get some purchase on.

- Who are your favourite historical comedians/people?

Heh, think I just answered that. I suppose you could add anyone who brings us to a closer approximation of the truth, Galileo, Newton, Hooke, Darwin, Vladimir McTavish et al.

- How would you describe your act?

Probably not in the way that others would describe it? I was in Fremantle the other night, or was it Perth? – regardless, the pre-show blurb had me down as ‘jovial’. ‘Jovial’? This has to be a consequence of the performers perennial dilemma – I want to be loved, I want to be accepted – I want to rock the boat, I want to rebel. But seriously ‘Jovial’? Fuck off!

- How do/did you go about writing material?

An idea, then one word tends to follow the other, just get it down, don’t think about quality, just flow – don’t stop. Then the hard part – re-write, re-write, and re-write again. Then the harder part, re-write, re-write, and… well, you get the idea. Don’t be precious – you will always write more. Your imagination really is bottomless. Starting from the premise you will throw away 98% of everything you write is a very good place to start. Oh, and it’s a good idea to learn some rules as it’s only by knowing the rules which allows you to break them. One last tip is that you are always a better writer than you are a performer. Look back over old stuff every now and again – your performance skills will have improved since you stopped doing it, so try doing it again.

- Tell me about the audiences, how did they respond to you?

Well, for the most part, wonderfully so – it would be strange to have done this for coming up to thirty years if they hadn’t? That said, I’ve died on my arse enough times over those thirty years, and expect I will do so again. It’s the fear of that which still fills me full of adrenalin whilst waiting in the wings – waiting, waiting for your name to be called, waiting to be called to account, waiting to be found wanting, waiting to be found out.

- Did you ever come across audiences who held questionable views? I know The Tunnel’s* punters could be really challenging, were there any others that you can remember? [*The Tunnel Club – an infamous London Club opened in 1984 by the equally infamous Malcolm Hardee. A.S.]

I remember standing at the side of the stage at ‘Up the Creek’ being introduced by Malcolm Hardee. The crowd were baying. He had his cock out. He said “Can’t remember this next fuckers name? Some piece of shit from up North?” I handed my pint to the guy standing next to me, “Hold this for me, mate – I won’t be long”. It was Jools Holland. I wasn’t long.

Closer to home I recall organising a benefit for striking Ambulance Workers and their families in Newcastle upon Tyne – they’d brought along their children, too. I was MC and had just introduced an act called Buddy Hell. His real name was Ray Campbell. He wore a beret and had an American accent. He was black. As I walked off the stage one of the striking Ambulance workers, his daughter on his knee, said to me, “Fuckin’ hell, who booked the fuckin’ Darkie?” I went back on stage and called them all a bunch of cunts. That’s what they were, a bunch of fucking cunts. Do you remember that, Ray?

- Were there any gigs you really hated?

Yes, ‘Up the Creek’, being introduced by Malcolm.

- Were there any gigs you really enjoyed doing?

Yes, ‘Up the Creek’, being introduced by Malcolm.

- (If you are no longer performing) When did you stop performing and why? Do you miss performing? OR (If you are still performing) What changes have you witnessed since you began performing? Have things changed for the better or worse?

I couldn’t stop performing. Ever. I need to do it now. It controls my emotions, the way I feel. Without performing I’d quickly descend into depression. If the backside fell out of the comedy industry I’d still do it, for nothing, in an upstairs room in a pub. As for changes, well, money changes everything. The need to pay a mortgage and bills – or feed kids – transforms the performers dilemma. ‘I want to be loved, I want to be accepted – I want to rock the boat, I want to rebel’ gets the following added to it: ‘I really need to get booked at this club again’. We need to find ways to ameliorate the last sentence. Maybe the only way that happens is that the arse falls out of the comedy industry and we all start doing it for nothing, again, in an upstairs room in a pub?

- Is there anything else you would like to add?

I need to be braver, both in my writing and in my performance – but I still want to look cool.

Anvil Springstien.

August 2013